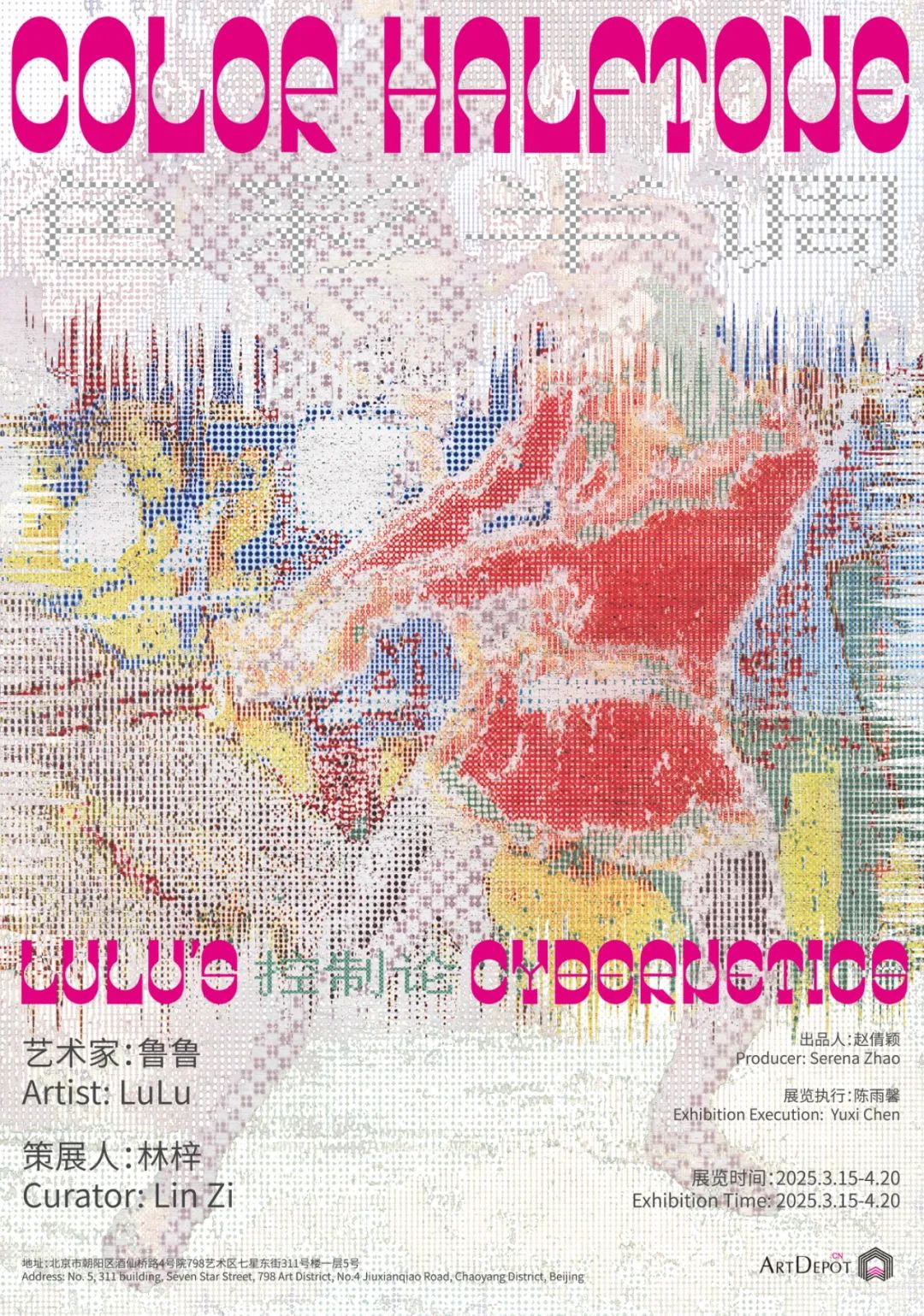

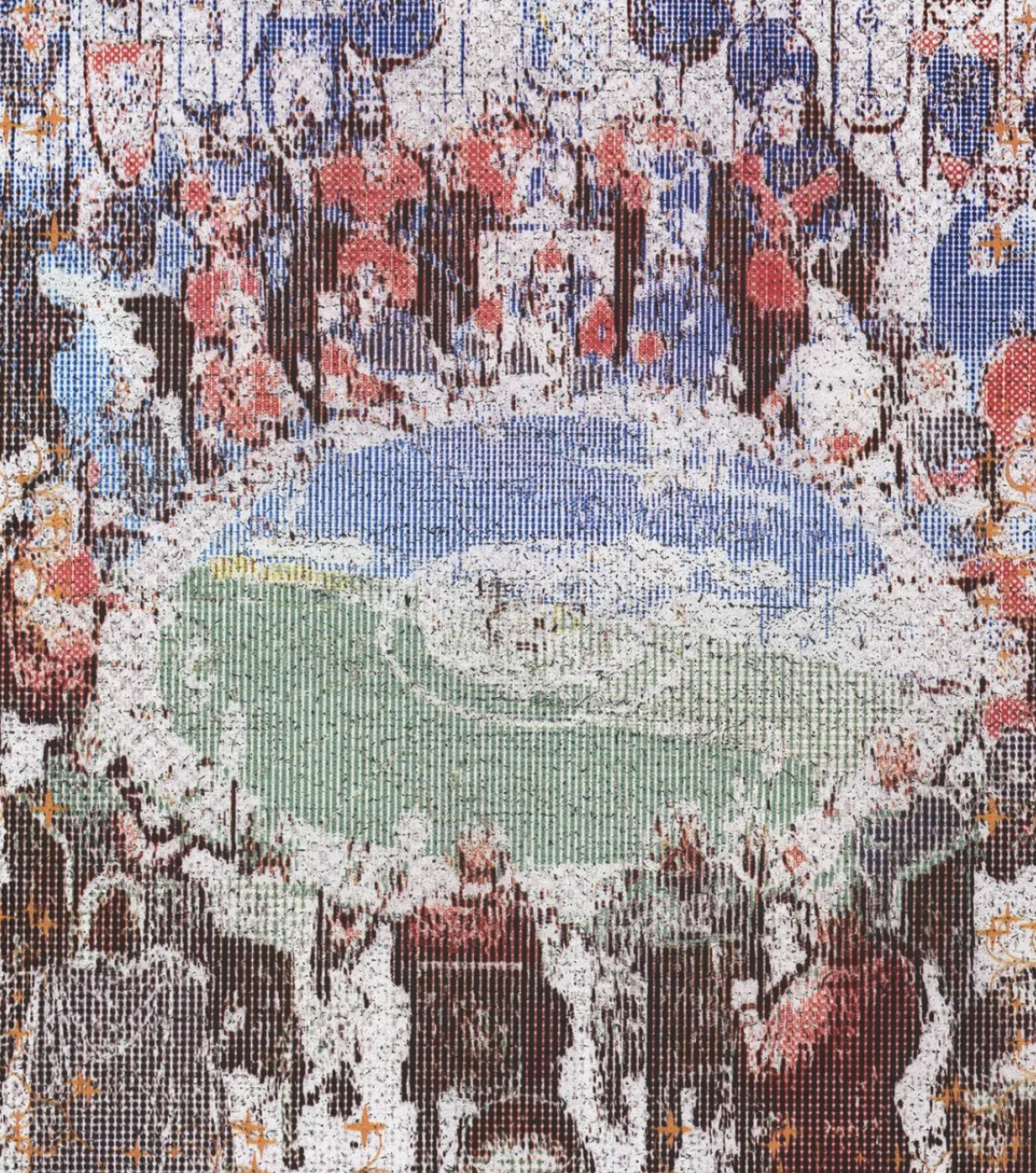

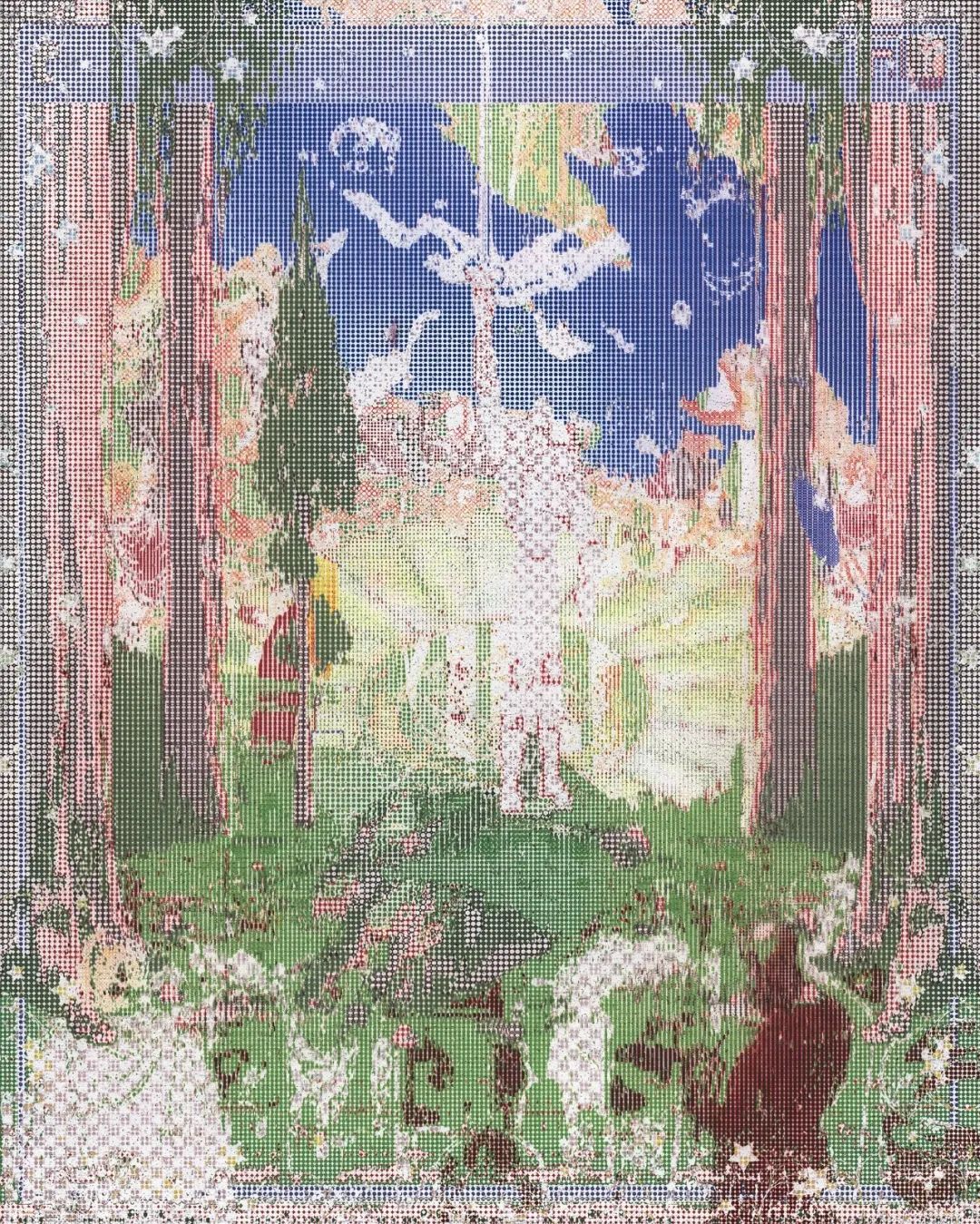

ArtDepot is pleased to announce that it will present “Color Halftone,” the first solo exhibition of selected easel paintings by the artist Lu Lu from 2024-2025 at the 798 Art District space in Beijing. The exhibition will open on Saturday, March 15, 2025 and will run until April 20, 2025.

Preface:

Color Halftone is an image processing technique that transforms continuous-tone images into images composed of dots of varying sizes and colors. This long-standing technique in the printing industry essentially utilizes the mechanical characteristics of printing presses to analyze and simulate images. The above content is derived from Digital Halftoning by Robert Ulichney, widely regarded as the "bible" in the field of halftone technology. Published by the MIT Press, it is a classic work on digital halftoning.

The term "Color Halftone," a specialized technical phrase from the printing industry, would typically remain outside the purview of laypeople, yet it piqued my interest. This curiosity stemmed from my attempt to understand what Lulu's work truly entailed. To what extent should his creations be classified as paintings? And does his work hold any significant value? After a month of research and dialogue with him, I ultimately uncovered the concept of "Color Halftone" and its profound relevance to his artistic endeavors.

One prerequisite for understanding Lulu's work is for the viewer to recognize how the majority of easel paintings are created in the year 2025. It must be said that, across all categories of painting except non-representational art, the image plays a central role in the artistic process. Beyond the habitual collection of images from both the physical and digital realms by artists, the manipulation and montage of images in Photoshop, the projection of images onto canvases to guide the painting process, and the combination of elements from multiple images on the canvas are all commonplace practices among today's painters. In this era where images, or more specifically, technological images, reign supreme, even artists—the last bastions of the "sacredness" of traditional imagery—are not immune to the deluge of technological images that impact their perception and practice. In other words, the core medium of the artist's work has subtly shifted from the canvas to the computer, with the most crucial aspects of image-making now taking place on the digital screen.

The aforementioned issues have long been prevalent among artists, yet the majority choose to remain tight-lipped about them. Meanwhile, most viewers continue to hold an unwavering belief in the "sacredness" and "purity" of traditional hand-drawn images. Consequently, few have come to realize that what we call painting has subtly transformed into a form of "image-making," with the distinction lying in the balance between "creativity" and "technicality." It is here, where others opt to sidestep the issue of image-making, that Lulu has chosen to confront it head-on.

One day, Lulu said to me, "Image-making is always the result of a game of compromise between humans and machines." He also offered a commentary on the software Adobe Photoshop, stating, "Photoshop is an external form through which humans use the methods of printing to understand technological images." He explained that many features within Photoshop, such as layers, liquefaction, Gaussian sharpening, and color halftoning—all terms that are also functionalities within the software—can trace their origins back to the development of the printing industry in the 19th century. For Lulu, Photoshop is not merely a software for manipulating image effects; in a McLuhan-esque sense, it also inaugurates a way of understanding images. This approach is entirely distinct from the way the average viewer comprehends images through narrative, symbolism, or form. Instead, it views images from a more fundamental, technical, and essential perspective: layers, color gamuts, MRI, granularity, color halftoning... In other words, the user of Photoshop is compelled to understand images in the manner of a drafting engineer from the 19th to 20th-century printing industry, which is to say, from the technical perspective of the printing press.

It is precisely here that Lulu diverges from the majority of artists. While most artists regard Photoshop as a "tool for achieving the desired image effects," Lulu seeks to genuinely understand and construct images from the machine's perspective through the aforementioned approach. This endeavor marks the inception of his series of works. Specifically, Lulu aims to minimize his own decision-making throughout the image-making process and reduce the manual traces he leaves on the canvas as much as possible. Instead, he allows the characteristics closely tied to technology within Photoshop and UV printers to play a maximal role in determining the final appearance of the image. Among these, the most representative method of understanding is "color halftoning."

"Color halftoning" signifies a way of describing and comprehending images entirely from the perspective of printing technology, as all newspaper printing machines produce images by contacting the material (template) with a vast number of ink-dipped "needles," which are then transferred onto paper. In other words, all images appearing on paper, regardless of their clarity, can be reduced to individual "dots," and the term that describes the relationship between the density and color of these "dots" is "color halftoning." One might wonder why Lulu, born in 1995, would be concerned with printing technology from the 19th century to the present. The answer lies in the fact that the UV printers widely used in the field of image output today still adhere to this principle.

The UV printer used in Lulu's work (CaShen UV Flatbed Printer Model 3220) employs Konica Minolta printheads. "A single pass of a printhead actually prints a width of 2mm, which is referred to as 1pass (one pass). If 1pass printing does not meet the desired ink droplet density requirements, we then print this 2mm multiple times to increase the ink droplet density and improve print quality." This information comes from a printing factory owner who collaborates closely with Lulu. The standards for "ink droplet density requirements" and "improving print quality" mentioned by him are based on our standards for the quality of traditional images. Lulu's meticulous attention to concepts like "color halftoning" is aimed at breaking away from this "human-centered traditional aesthetic" and embracing a "technology-centric post-human aesthetic."

However, at the specific technical level, how can an artist ensure that their work revolves around a "technology-centric post-human aesthetic"? This often means that the artist must force themselves to overlook much of the content-level information and instead adopt a perspective highly sensitive to the medium for thinking and action. In his self-statement, Lulu mentions: "In my creative practice, all existences, whether concrete or not, are regarded as a medium." He says that the initial motivation for creating a piece often comes from information pushed to him by AI on platforms like Xiaohongshu. "For example, I recently investigated the history of the car model image and often discussed it with others, so recently Xiaohongshu has been pushing a lot of car model images and information to me daily; more often, my reception of such information is entirely passive, such as when you (Lin Zi) brought up Lacan and Flusser in conversation with me, which was completely unexpected, but the next day AI also pushed similar information to me." Therefore, Lulu places more importance on this type of information because he hopes to participate as little as possible in the decision-making process of the work.

Thus, Lulu saves the images pushed to him by these platforms and then observes the identities of these images. Many images contain similar informational elements but come from different contexts; another common scenario is images from the same context that exhibit different visual elements due to significant temporal differences. What Lulu is concerned with is the issue of the identity of these images behind their similarities and differences. The issue of an image's identity is a complex aggregation of the context in which the image currently exists, the context in which it was created, and the historical and social factors it has undergone during its dissemination. One of the most common transformations in image identity is that of art historical images—for example, a specific work by Botticelli from the Renaissance period, which for a long time was only circulated within Western art academies, became recognized by East Asian art practitioners in the late 19th century as an image "representing Western artistic achievement," and then in the era of globalization post-Cold War, became a representative symbol of "Western art" or "art" in the public consciousness globally. Throughout this process, the content of the image itself did not change, but the identity of the image underwent a tremendous transformation—this is where Lulu's interest lies in the image materials at the start of his work.

Subsequently, Lulu takes two or more images from this domain as materials and performs a series of operations on them in Photoshop. These operations can be simplified as follows: selecting two images with vastly different identities but containing similarities in content or form, using various algorithm-based methods in Photoshop to analyze them, including analysis at the "color halftoning" level; finally, superimposing the various layers resulting from the analysis back into the same image, preserving as much as possible the randomness that arises from this process. Lulu then sends this file to the owner of the UV printing factory, visits the factory on a certain day, communicates with the owner as necessary, and witnesses the work entering the printer several times. As mentioned earlier, the printer uses color as a basic parameter, printing layer by layer on the canvas surface, and ultimately completing the physical layering of pigments. At this point in the process, the work is essentially complete.

When the work is finally hung on the gallery wall, viewers can easily recognize the significant differences between the appearance of Lulu's paintings and the majority of paintings on the market—through the narration of this article, we realize that this difference is not merely due to the style and visual aspects of the work: those layered effects are not for decoration, and the appearance of figures is not for narrative purposes. Through the above narration of this article, we should see that Lulu's entire approach to work, his perspective on problem-solving, and his acute awareness of the medium all bring him closer to the identity of a contemporary artist rather than a traditional painter. Although Lulu's works ultimately appear before the viewer as easel images, the work he does is closer to that of a sculptural artist. The value of Lulu's work clearly does not lie in the amount of work and training he has invested in the technical aspects of painting, but rather in appreciating the trade-offs and coordination he makes between the variables of technicality, randomness, contingency, and readymade (nature) with a "post-human-centric perspective" and a "McLuhan-esque medium awareness" as the main subjects.

Taking "color halftoning" as a technical entry point, Lulu has conducted extensive research and experimentation in the complex field of digital cartography, and a deep understanding of technology has become a prerequisite for constructing a "human-machine relationship" in his work. The term cybernetics used in the title of this article also stems from the bidirectional balancing relationship Lulu achieves with technology in his work, as mentioned in the previous paragraph. The control between humans and technology is a complex paradoxical relationship, and it is not the case that "artists only use technological devices as tools to achieve their own ends" that they occupy an active position in this game of control—on the contrary, as Vilim Flusser pointed out: the more artists handle this relationship in such a way, the more hopelessly they fall under the control of technology. Lulu's approach, which seems to let "machines and algorithms take the lead," is actually about securing an active position for himself in this human-machine game. And this is precisely the core of what cybernetics as a discipline studies.

For the author, Lulu's work is very sincere and forward-looking. In the future genealogy of easel painting, a category defined by a perspective similar to Lulu's will certainly emerge. As digital technology becomes more deeply embedded in the social life of contemporary people, the awareness of the medium, reflection on and critique of technology will inevitably become an important direction for art to justify its own existence—this understanding will become a consensus among global art practitioners, without any regional color. While the majority of painters avoid discussing the extent to which technological tools have permeated their working methods, Lulu confronts this issue through the artistic practice of cartography and relentlessly critiques and demystifies painting (this ghostly conceptual form) through the working method of technical cartography. It is in this direction that Lulu's cognition and practice completely surpass those of the vast majority of his contemporaries. The value of his work will gradually become apparent over time, and the traditional medium of canvas will find its new legitimacy through "the critique and demystification of painting."